By Ann Pettifor

Payday and pawnbroker lending in the UK has risen from £1.6bn in 2008 to £5bn in June 2013.[1] While this lending activity is still a small percentage of UK GDP, nevertheless payday lending is one of the fastest growing industries in the UK.

Because of austerity policies on the one hand, and inflation on the other, British incomes are still falling in real terms. And because the big commercial banks are unable and/or unwilling to lend to all sectors – payday lending is expanding fast. Those who do not have enough money to get by on a day-to-day basis, and who are unable or unwilling to cut back on spending – are turning to “legal loan sharks”[2] that charge usurious rates of interest on short-term loans.

This borrowing is often undertaken by individuals under pressure, and without consideration of the real cost of the loan or debt, thus piling up problems for themselves in the future. It is also ineffectively regulated borrowing – with government, the Bank of England and other regulators turning a blind eye. Worse, this debt is accumulating within a deflationary environment (i.e. wages have fallen and prices are now beginning to fall). In these circumstances the cost or value of debt rises. (In an inflationary environment the reverse happens: the value of debt falls.)

That is why we dub the UK economy the: “Alice in Wongaland economy”.

“Interest rate Apartheid”

Wonga and related moneylenders are providing money to people because Britain’s High St banks won´t. Payday lenders bridge the gap between bill payments and payday for people struggling with rising living costs.[2]

Their services come at a high price. While annual percentage interest rates (APR) are indeed a misleading measure for short-term loans, the Guardian estimates interest rates on payday loans at between 30% and 35% per month.[3]

Max Keiser, popular financial broadcaster has coined the term “interest rate apartheid.” He is describing a system where some individuals can borrow at lower rates, while the under-capitalised are forced to borrow at exorbitant, usurious rates.

“Usury – the act or practice of loaning money at an exorbitant..or unlawfully high.. rate of interest” — Collins English Dictionary, Millennium Edition.

Payday lenders – at micro level – are today recreating the conditions of the past decade during which ‘sub-primers’ were charged high interest rates for loans that were ultimately unpayable. And we all know how that ended…

But the system entrenches a damaging divide for an economy as unbalanced as Britain’s. While banks and other financial institutions are able to borrow at very low rates from central banks (often for speculative purposes) they nevertheless lend to other, more productive sectors of the economy at much higher rates. In Britain, banks and other financial institutions can borrow from the BoE at 0.5%. However, according to the Bank of England’s latest Trends in Lending the average indicative rate for smaller SMEs is nearer 5%.[4] By means of this ‘carry trade’ private banks use the resources of public banks to recapitalise their institutions and clean up their balance sheets. The economy’s small firms are charged much higher, real rates.

No wonder levels of investment in Britain are so very low.

Fragile UK Recovery based on payday loans

Recent growth numbers for UK services, manufacturing and construction suggest that Britain is recovering after the recession double dipped in 2011/12. Private consumption has risen. However wages remain low. According to the Office for National Statistics household income in Britain declined before the crises between 2001/2 and 2006/7 by 1.4% per year. Since the recession, income before tax has declined at an average rate of 2.1% per year, according to the BoE. If income is not rising, how is increased consumption financed?

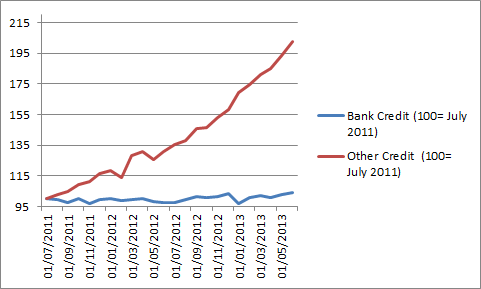

The Bank of England Money and Credit statistics show that financing is increasingly derived not from mainstream banks, but from other credit institutions –such as pawnbrokers or payday lenders.

The Bank’s statistics[5] reveal that amounts outstanding to conventional banks and building societies fell by 13.13% between July, 2011 and 2013. In stark contrast the amounts outstanding with “other” creditors (payday lenders etc.,) increased by 18.75% over this period. In other words, borrowers were effectively deleveraging debt owed to conventional banks and building societies over this period. At the same time payday borrowers were releveraging debt owed to moneylenders that are effectively unregulated.

Between July and September, 2011, lending by conventional banks and building societies was negative. Borrowers paid back £138 million more than they borrowed. At that point High St bank borrowers were deleveraging.

Over this same period, lending by the unregulated sector was positive. In the autumn of 2011, when other borrowers were deleveraging, payday borrowers were leveraging debt; increasing borrowing over repayment by £33 million.

Between April and June 2013, borrowers from High St banks were releveraging again. Lending was positive, i.e. borrowing exceeded repayment to banks by £1,01bn.

Over the same period borrowers from unconventional lenders releveraged too, but by a slightly higher margin than that for High St. banks: £1.05bn.

The changes in net lending show that both mainstream and less regulated moneylenders have increased lending. But payday lenders have expanded lending by more than High St. banks have. Given that their lending is far riskier and also much more costly, this development signals danger signs.

The graph below shows the rapid increase in the growth of this effectively unregulated moneylending sector.

697247-System__Resources__Gallery_Image-789200

Created by Citywire Money, David Campbell 15th August 2013 based upon Bank of England Money and Credit data.[6]

So far from de-leveraging debts, between 2007 and 2012, in the depths of the crisis and as incomes were falling (or because incomes were falling), British households increased their borrowing every year by 1.2%.[7]

This behaviour contrasts with that of Germany where increases in household incomes were matched by declining household debt between 2007 and 2011. Even the US is somewhat ahead of Britain as household debt has been deleveraged since the recession despite falling household incomes.[8]

In comparison to Germany and the US, the British “recovery”, based as it is on consumption and risky, very expensive borrowing, seems illusory and dangerously fragile.

[1] Bank of England Money and Credit database [2] Stella Creasy “A cap on the cost of interest will curb the loan sharks” The Independent Online: http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/stella-creasy-a-cap-on-the-cost-of-credit-will-curb-the-loan-sharks-8680019.html [accessed 23rd August 2013, 14:35] [3] Personal Finance Research Centre “The impact on business and consumers of a cap on the total cost of credit”, University of Bristol, 2013 Online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/136548/13-702-the-impact-on-business-and-consumers-of-a-cap-on-the-total-cost-of-credit.pdf [accessed 22nd August 2013, 12:47]. [4] Sean Farrell “Pawnbroker stops payday loans and describes Wonga´s rates as `ludicrous’ in The Guardian 12th August Online: http://www.theguardian.com/money/2013/aug/12/pawnbroker-payday-loans-wonga-rates [ accessed 22nd August 2013, 17:23] [5] Bank of England “Trends in Lending” July 2013, p.8 Online: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/other/monetary/trendsjuly13.pdf [6] Bank of England Money and Credit database [7] David Campbell “How Wonga is driving the recovery” for City wire Money 15th August 2013 Online: http://citywire.co.uk/money/eight-graphs-subprime-uk-how-wonga-is-driving-the-recovery/a697252#i=4 [accessed 22nd August 2013, 17:21] [8] Bank for International Settlements “Long Series on credit to private non-financial sectors” database [9] Ibid.

9 Responses

Mick, thanks for sharing this exchange with David Campbell…the chart you refer to is not included in our blog…and so your query is rightly aimed at him, and not at us. However, my understanding is that he calculated, and then compared the rate of growth in lending by non-standard MFIs (monetary financial institutions) over the year, and noted that the growth was well ahead of standard MFI lending…which is the story that Wonga tells too…So am not sure of the problem here.

In your footnotes [6] and [7] you cite David Campbell’s Citywire Money Manager article of 15th August 2013 “How Wonga is driving the recovery”. In his footnote to graph 5 in that article he says “Consumer credit creation is suddenly booming at 14.6% growth in June – the second consecutive month of +10% rises”:

http://citywire.co.uk/money/eight-graphs-subprime-uk-how-wonga-is-driving-the-recovery/a697252#i=5

I’ve just had an email exchange with him about the source of these figures and my question and his reply are set out below.

I asked:

“Dear David Campbell,

In your Citywire, Wealth Manager article of 15/08/13 – ‘Eight Graphs: Subprime UK – how Wonga is driving the recovery’ – in the footnote to graph 5 you say “Consumer credit creation is suddenly booming at 14.6% growth in June – the second consecutive month of +10% rises”.

However, in the latest BoE statistical release ‘Money and Credit: June 2013’ Tables J and K give monthly, 3 monthly and annualised growth rates for June 2013 of 0.3%, 5.0%, and 3.6% respectively.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/Pages/mc/2013/jun/default.aspx

I’d be grateful if you could let me know how you obtain your figures and how they correlate to those of the Bank?

Thanks”;

to which he replied:

“Hello

This was the best part of a month ago now but from memory I believe I just calculated the most recent data relative to the year before (from the monthly BoE release) – I don’t know if the BoE adjust for seasonality or uses the three-month underlying trend or similar, which may be more sophisticated than my treatment”

The BoE have both seasonally adjusted and non-seasonally adjusted data for consumer credit available, however I can’t find any that seem to mirror his figures. As you have cited him I wonder if you have any insight into how his figures may have been calculated?

Thanks

The problem with our capitalist UK economy is that consumption is predicated by the need for a fairly even distibution of real incomes to support it – basic economics! This clearly is not happening. Secure full-time jobs are disappearing, real incomes are falling across the board, the middle classes are having the financial life squeezed out of them, and the poor are in the hands of the pay-day loaners. Cheap money is being diverted from those who need it i.e. businesses and individuals,to those who don’t, i.e. financial insitutions. QE and low interest rates are leading to a massive re-distibution of income to the already rich, and inflation in asset prices that is the antithesis of a healthy capitalist economy. And – when will all this debt be repaid!

Payday lenders are in a competitive market and charge an appropriate rate, The banks in UK and US have been very effective and destroying their competitors, in UK the building societies were demutualised and then destroyed by being forced to lend at crazy income multiples to compete with the politically connected Northern Rock. In US the savings and loan industry was destroyed by wall street criminals leaving the current banking market, we are trying to tackle international usury they own our government and they own the regulators. We need to recreate building societies and credit unions people should have choices and that will bring down prices. When you have open borders for people and capital living standards in UK will converge to the lowest levels in Europe, this is what NAFTA did to the US we will suffer the same. de-intermediationn is required, banks borrow from one man and lend to another we must cut out the middle man

The Law of One Price is the free-market propaganda tool which claims ‘we are all equal, all in this together’. So I, like anyone else can go into Tescos and buy a tin of beans or a newspaper at exactly the same price as anyone else.

Not so with credit: Every customer has to provide personal details, and is charged a differing interest rate accordingly. A clear a violation of the Law of One Price, yet our gung-ho free-marketeers don’t draw the obvious conclusion. Lending money is NOT like selling baked beans, and needs to be regulated toughly and supervised closely.

Will that happen? Will the neo-cons clamour for it? LOL

The fact that expansion in non-regulated “bank” lending has been much the same as the expansion in regulated bank lending recently is interesting and a bit alarming. Thanks for that.

Re the idea that there is something wrong with banks charging SMEs 5% or whatever, I’m not sure about that. The reality is that lending to SMEs is about twice as risky as lending where property is offered as collateral, and that is taken account of in the Basel risk weighting rules.

A bank manager:-

“A person who will lend you an umbrella when the sun is shining and demand its return when it is raining”

“Wonga and related moneylenders are providing money to people because Britain’s High St banks won´t”

That’s not the case at all. The moneylenders lend money because there aren’t enough jobs paying a living wage in our corporatist neo-liberal hell of an economy.

Adverse credit and short-term lending is a specialist market – something the High St banks are no good at. They tried to move into the market during the boom times and quickly retreated once they got their fingers burnt.

If you remove the payday moneylenders then all that happens is that people charging higher interest rates turn up – those with baseball bats and guns.

The root cause of the problem is a lack of jobs and income – something not mentioned at all in your article. Disappointing.

Knuckles duly rapped. We are just struck by the speed at which non-mainstream lending is rising relative to High St lending….and of course understand the driving forces (the lack of employment and falling incomes/cuts in welfare)…but its really scary given this is debt on which very high rates of interest are charged, and compounded.