T. Sabri Öncü ([email protected]) is an economist based in Istanbul, Turkey. This article was written on 2 July 2016 and first published in the Indian journal Economic and Political Weekly on 16 July 2016.

The Lehman moment is the moment when Lehman Brothers—one of the largest investment banks in the United States (US) at the time—collapsed. The collapse happened on 15 September 2008. Almost nobody disagrees with that the Lehman moment has been the most important moment in the ongoing global financial crisis that started in the summer of 2007, at least, up until the Brexit moment.

What is Brexit Moment?

The Brexit moment refers to the 23 June 2016 referendum in the United Kingdom (UK) in which the Britons voted on whether to remain in or to leave the European Union (EU). Its outcome became official on 24 June 2016.

Naturally, there were two sides. The “Bremain” side, supported remaining in the EU, and the “Brexit” side, supported leaving the EU. The Brexit side beat the Bremain side 51.9% to 48.1% on 23 June, unexpectedly. The next day, the Brexit moment hit the global financial markets leading to major drops in almost every equity market around the globe. And, since then, the internet has been flooded with unidentifiably many articles analysing sociological, psychological, political, geopolitical, economic, financial and other difficult-to-imagine aspects of Brexit.

This article comes from two of those articles. There was one statement from each that struck me. The statement from the first article, attributed to the Allianz Chief Economic Advisor Mohamed El-Erian, is: “Brexit: Not a Lehman moment.” The statement from the second article is: “Brexit is a Bear Stearns moment, not a Lehman moment.”

Prior to Lehman moment, there were three other important moments. The first Bear Stearns moment (20 June 2007), BNP Paribas moment (9 August 2007) and the second Bear Stearns moment (14 March 2008).

Shadow Banking

Simply put, shadow banks are non-bank financial institutions which behave like banks. They borrow in rollover debt markets, leverage themselves significantly, and lend and invest in longer-term and illiquid assets. The difference between the two is that, unlike banks, shadow banks cannot create deposits—that is, money. If we leave this aside, then the two are more or less the same.

The significance of this is that just as bank runs can occur on banks, shadow bank runs can occur on shadow banks.

A bank run is rioting of the bank’s depositors—the most important and largest section of the bank’s short-term creditors—at the bank’s door to get their money out. A shadow bank run is more or less the same. Except that, since shadow banks have no depositors, it is their short-term creditors who riot at the door. This riot takes place electronically at a virtual door. It is not visible, because it is not physical.

The reason why those who claimed Brexit was not a Lehman moment must have been that there was neither a bank nor a shadow bank run at Brexit moment.

First Bear Stearns Moment

The signals of the first Bear Stearns moment became noticeable early 2007. Like Lehman, Bear Stearns was one of the largest investment banks in the US at the time. When the real estate bubble in the US started to burst in the first quarter of 2006, the subprime mortgage market began to deteriorate.

The first casualty were two highly levered Bear Stearns hedge funds. They were shadow banks speculating in subprime mortgages by borrowing short-term funds in the repo market and pledging their mortgages as collateral.

With the deterioration of the subprime market in early 2007, creditors began asking these funds to post more collateral by June 2007. When the funds failed to post more collateral, Merrill Lynch seized $850 million of their assets and tried to auction them on 19 June 2007. When Merrill Lynch was able sell only about $100 million of these assets, the illiquid nature and the declining value of subprime assets became evident. The next day, these funds collapsed.

This is the first Bear Stearns moment.

BNP Paribas Moment

Although the collapse of these two funds did not freeze the repo market, it increased the fears of counterparty risk and made the problem systemic.

Here, the key word is fear. When fear hits financial markets, it spreads.

In early August 2007, a run started on the assets of three special investment vehicles (SIVs) of BNP Paribas. These SIVs were bankruptcy-remote entities financing their subprime holdings through issuance of asset backed commercial paper (ABCP). On August 9, BNP Paribas suspended redemptions from these SIVs when their ABCPs lost their liquidity and became non-tradable. This caused the entire ABCP market to freeze. When fears of counterparty risk spread through markets, all short-term debt markets froze, only to open after central banks injected massive amounts of liquidity (Acharya and Öncü, 2013).

This is the BNP Paribas moment.

The BNP Paribas moment is what started the ongoing global financial crisis. The reason why most people do not know about BNP Paribas moment is that it effected the US markets mostly. Lehman moment is better known, because it globalised the crisis.

Second Bear Stearns Moment

It is all about fears and, beginning late Monday, 10 March 2008, fears spread about liquidity problems at Bear Stearns, freezing the repo markets in which Bear Stearns was funding its illiquid assets.

This happened on 13 March 2008. Then, on Friday, 14 March 2008, on the second Bears Stearns moment came.

On 14 March, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York agreed to provide a $25 billion loan to Bear Stearns to save it, sending the signal to markets that Bear Stearns was dead. Failing to save Bear Stearns on Friday, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York arranged a costly marriage between Bear Stearns and JP Morgan Chase on Sunday, 15 March 2008, about two years after which Bear Stearns name went into oblivion.

This is the second Bear Stearns moment which laid the ground for Lehman moment.

Fear Indices

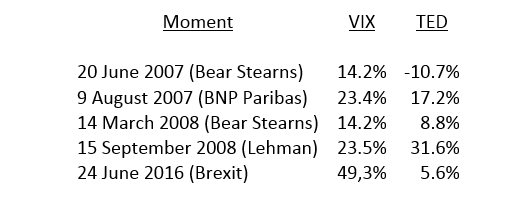

There are many fear indices in the global financial markets and I will compare the above described four moments—namely, the two Bear Stearns, BNP Paribas and Lehman moments—with the Brexit moment based on two indices— VIX and the TED Spread.

Their main significance is that they are publicly available and daily data for these indices go way before the onset of the ongoing global financial crisis.

A third index I will touch upon is SKEW, but unfortunately, its daily history I was able to obtain starts only after 2010.

VIX: VIX is the ticker symbol for the Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index, a measure of the 30-day volatility of S&P 500 index options. It is constructed using the implied volatilities of a wide range of S&P 500 index call and put options, and meant to be a forward looking measure of volatility. It was introduced by Whaley, a Vanderbilt University finance professor, and had gone through several modifications since its introduction in 1993. Often referred to as the fear index, it has been considered by many to be the world’s premier barometer of investor sentiment and market volatility.

TED Spread: The TED spread was born after Chicago Mercantile Exchange developed and introduced the Eurodollar futures contract in December 1981. When first defined, and traded, the TED spread was the difference between the interest rates for the 3-month Eurodollar futures and 3-month Treasury bill futures contracts. Indeed, ED is the ticker symbol of the Eurodollar futures contract. These days, the TED spread is the spread between the 3-month LIBOR and 3-month US Treasury bill rate. The TED spread is viewed as another fear index, because many view it as a measure of the perceived difference between the safety of lending to other banks and the safety of lending to the default risk free US Treasury by the banks of concern. A big jump in it indicates funding liquidity freezes, that is, “bank runs”, in money and credit markets.

SKEW: SKEW is the ticker symbol for the Chicago Board Options Exchange Skew Index, a measure of tail risk—that is, the risk of extreme events such as major crashes in equity markets. SKEW is calculated from a wide range of (out-of-the-money) S&P 500 index options and considered by many as the real fear index. Historically, it fluctuates between 100 and 130 and its historical maximum is 151. Its values beyond 130 usually indicates increased risk avoidance in financial markets.

Comparison of the Moments

Let me now compare the five moments based on VIX and the TED Spread as percent changes from a day earlier in the below table.

The very first conclusion from the table may be that Brexit moment is neither any of the two Bear Stearns moments nor the BNP Paribas moment nor the Lehman moment. It is a new moment. While based on VIX, the Brexit moment is the worst (given its impact on the global equity markets, this is expected), based on the TED Spread, the Lehman moment is the worst and the Brexit moment is just an ordinary event (given that the UK is neither a bank nor a shadow bank, this is expected also).

Two other observations are as follows. The first is that from 23 June to 30 June, the TED Spread jumped about 17.7%, which may indicate some funding liquidity issues. The second is that SKEW reached its all-time high of 151 on 28 June, which may indicate increased risk avoidance and market expectation of an extreme event, that is, growing fears.

Apart from all of these, most European banks are zombies. Since 23 June, the Italian bank shares crashed more than 20% and the Italian banks are dying one by one these days. Furthermore, the International Monetary Fund called Deutsche Bank (the largest German bank) the riskiest financial institution in the world as a potential source of external shocks to the financial system on 30 June. With few exceptions, the government interest rates are falling in almost every country, and even the long term Japanese, German and Swiss interest rates are in the negative territory. True, the world equity markets recovered their losses after the Brexit moment. But, this was because of the expected coordinated interventions by the world’s major central banks, which they fulfilled.

One of my favourite albums of all times is Gaudi album by Alan Parson’s Project. One of its song is La Sagrada Familia. Here is a part of the lyrics.

V.V. Acharya and T.S. Öncü (2013), “A Proposal for the Resolution of Systemically Important Assets and Liabilities: The Case of the Repo Market,” International Journal of Central Banking, January, pp. 291-349