Two rather unexciting news items were released this May. First, the ECB has kept the bank rate at 0.25 per cent as expected. The ECB board must, like the IMF, be concerned about deflationary tendencies in the Eurozone.

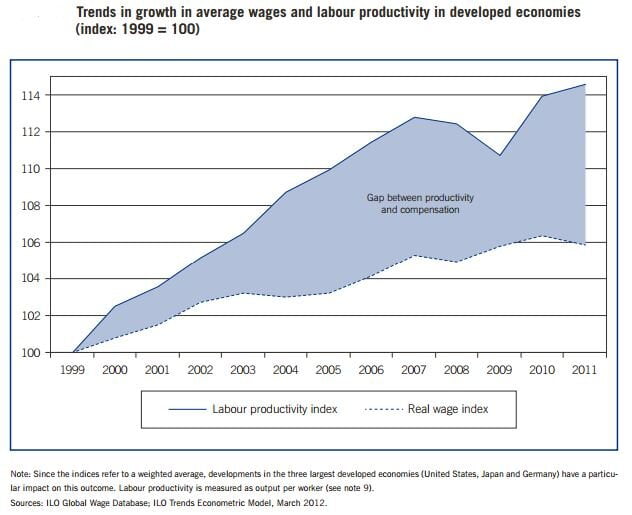

The second piece of news was that the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) presented a worldwide survey in Berlin this week-end concluding that

“The global economy needs co-ordinated action to raise living standards around the world. Seven years into the economic crisis has left structural damage to the global economy and the global workforce with more than 200 million people unemployed and many more struggling with low wages. Governments are in the grip of corporate power and are failing their people” said Sharan Burrow, General Secretary, ITUC.

OECD understands this as well. Mr Gurría, Secretary General of the OECD says

“…with the world still facing persistently high unemployment, countries must do more to enhance resilience, boost inclusiveness and strengthen job creation. The time for reforms is now: we need policies that spur growth but at the same time create opportunities for all, ensuring that the benefits of economic activity are broadly shared.”

The dissastisfaction with living standards persists most surprisingly in Germany, the alleged star of post-crises OECD economies, as reported by another OECD analysis.

What struck me reading this news is that few seem to make the connection between deflationary tendencies on the one hand, and low living standards on the other.

What is deflation?

We all know what lower living standards feel like. However, because we have never lived through a deflationary era, we know little and understand less about deflation. Just as inflation is “too much money chasing too few goods and services” deflation can be defined as a scarcity of money available for the purchase of goods and services.

In a deflationary environment, money becomes valuable because its supply is limited. Deflation has devastating impacts because the real value of debt and debt servicing costs rise which leads to a vicious cycle of low spending, unemployment, less demand and even lower spending.

With the transition of economies toward fiat money the problem of deflation was largely avoided. Money is created by commercial banks, in response to economic activity and demand.

Endogenous money production and we still deal deflation?

In modern economies the private bank sector creates most of our money. The accepted application for a loan creates the deposits that firms or individuals need for investments.

Additionally, central banks can increase liquidity for the private finance sector with QE as undertaken by the Federal Reserve, a move considered by the ECB. Low central bank policy rates for the private finance sector are supposed to encourage bank lending into economies with cheaper money. However the transmission system is not working well, as the IMF warns:

“A new risk stems from very low inflation in the euro area, where long-term inflation expectations might drift down, raising deflation risks in the event of a serious adverse shock to activity.”

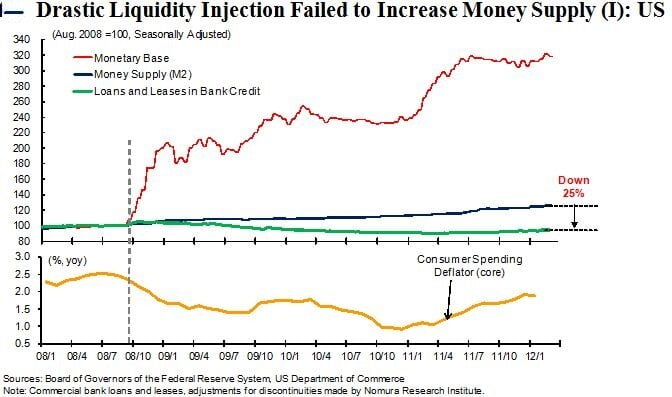

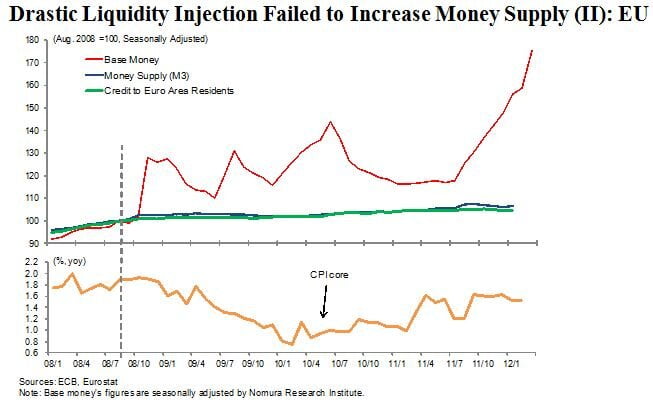

We know that central banks since the crisis have generated at least $16 trillion of liquidity. However this finance has not increased the money supply as the charts show below. The liquidity does not seem to have been directed at the real economy, and at stimulating investment and employment. Additionally living standards are not improving. Where is the connection? Why is liquidity not generating sustainable economic activity?

money supply US

money supply EU