John Weeks is co-convenor of Economists for Rational Economic Policies, EREP

Criticisms of gross domestic product as a measure of economic performance are common, even by mainstream economists, including winners of the so-called Nobel Prize in Economics. One need not be recipient of a prize from the Central Bank of Sweden to recognize that the details of George Osborne’s “recovery” indicate something seriously rotten in the British economic system.

A functioning national economy produces the goods and services demanded by its population. In part this is achieved through exporting a portion of domestic output in exchange for things produced elsewhere. In order to produce goods and services for home and export, companies must raise funds both for investment to construct facilities and for working capital. In addition, factories and offices require water, sanitary services and power. Once produced or imported the goods and services must be stored and transported.

Some of these activities are both inputs for production and used directly by households; for example, transport (public and private), water and electricity. To state it simply, in a well-functioning economy finance serves as a facilitator of production, construction and distribution. Similarly, estate agents and civil legal services exist to aid households and businesses in obtaining access to and producing goods and services.

This is what we should mean by the frequently used term “balanced economy”: production, consumption and investment drive an economy, with finance the facilitator (see article by Larry Elliott). In a balanced economy finance is an activity derivative from the fundamental task of employing, feeding, housing the population and keeping workplaces operating. I strongly suspect that most people think of our economy in this way.

When an economy is balanced we expect the growth of finance to reflect on a smaller scale the growth of non-financial activities. With this in mind, the statistics on the UK economy appear very strange, indeed. To grasp how strange, I divide GDP into two parts, “basic activities” and “facilitating activities”.

Into the facilitating category go all finance, real estate, accounting and legal services linked to these. Basic activities include production, transport and communications, public utilities (water, sanitation and power), and all other services from child care to haircuts. This is not a distinction between “productive” and “unproductive” activities (though the UK national accounts use a “production” “non-production” division).

My dichotomy is much simpler and less contentious, which an example shows. If we all built our homes on land we inherited, we would have no need of estate agents. All but a very few purchase homes or rent, so estate agents provide a necessary and useful service. Estate agents exist because people need a place to live, not the reverse.

The same applies to finance. If companies producing goods and services for households and other business cover their need for investment and operating funds from retained earnings, we would expect the financial sector to shrink to a very small portion of the economy.

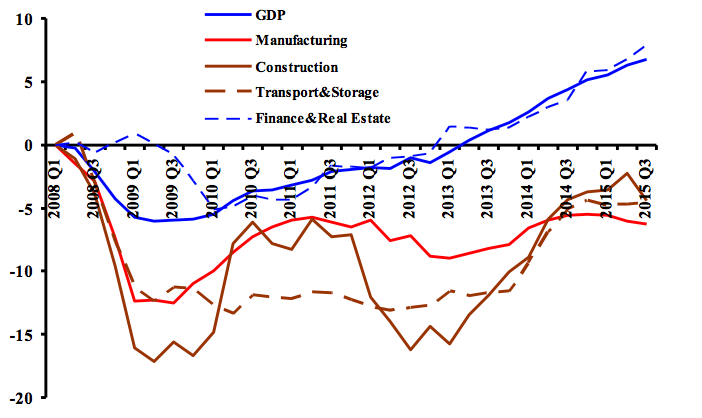

This view of the economy may seem very reasonable and logical. However, the behaviour of the UK economy refutes it, as the chart below demonstrates. The economy reached its pre-crash peak at the beginning of 2008. Now, 7½ years later manufacturing activity remains 6% below that peak and weakening further, construction 4% below, and storage and transport 5% down.

And GDP is up by 7%. How is it possible that producing things, building things and moving them around are all lower, but GDP is up? The mystery deepens when we discover that financial activities and real estate almost exactly track the measured increase in GDP, up 8%. With making, moving and building all down, how do the financiers and estate agents find more business for themselves?

During the first nine months of 2015 finance, insurance and real estate together accounted for 14.6% of GDP, only slightly less than manufacturing and construction together (15.8%). To put this 14.6% into perspective, it was one-quarter of private sector GDP – one out of every four pounds of private sector income and expenditure went to “facilitating” activities, up substantially from before the crisis of 2007-2008.

If those numbers suggest that the tail wages the dog of the UK economy, further inspection of the chart solidifies that interpretation. While finance and real estate followed the rest of the economy down during 2008-2009, subsequently “facilitating” and “basic” activities have been ships that pass in the night, each going its own way.

Thus, the mystery deepens. It appears that for some unknown reason the UK economy requires an increasing amount of “facilitation” to service the basic sectors. However, we discover that the growth of what should be facilitating production and distribution of goods and services bears no relationship to the growth of those goods and services.

Real GDP & its components, percent changes compared to 2008Q1

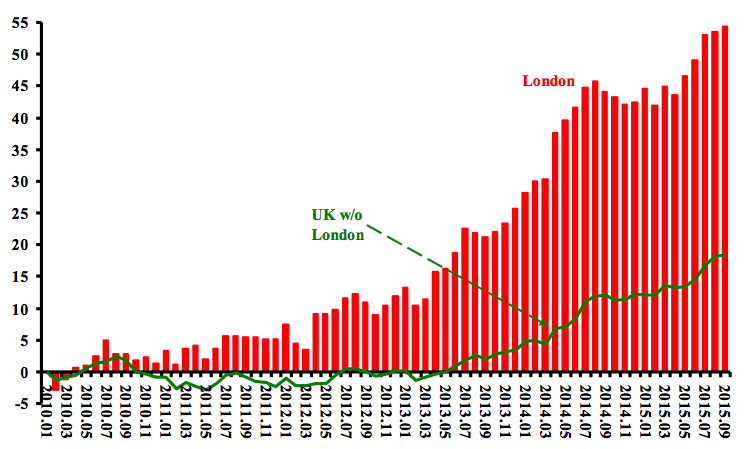

One word encapsulates the solution to the mystery – speculation. A second chart indicates one dimension of this speculation, in the housing market. In September of this year London housing prices rose to 54% higher than in January 2010, compared to 18% for the UK housing market excluding London.

The annualized outside-of-London rate was 3.4% compared to the overall rate of inflation of 2.5% for the same period. This is a difference that might credibly be attributed to a relative shortage of housing. It should not be ignored that this shortage results largely from lack of construction of new dwellings under the current government, combined with that government’s incentives on the demand side of the housing market.

Some differential between London and the rest of the country should be expected. However, we cannot credibly attribute an over 50% increase to “supply and demand”, especially since no other region experienced an increase of 30% or more (the “East” region came closest at 29%). The obvious explanation for the large London differential is speculation by both foreign and domestic buyers, fuelled by a dysfunctional financial sector. Here we have the explanation for a real estate sector expanding rapidly even as the supply of dwellings stagnates.

Over the last two years (24 months through October) covering Mr Osborne’s much-bragged-about recovery, net bank lending (loans minus repayments) to non-financial businesses totalled minus £13.6 billion. Loans to what the Bank of England defines as “small and medium-sized enterprises” received a positive but paltry £384 million, leaving “large businesses” with minus £14 billion.

One Response

I essentially agree- but can it be argued that finance and real estate is earning the UK income from activities abroad?