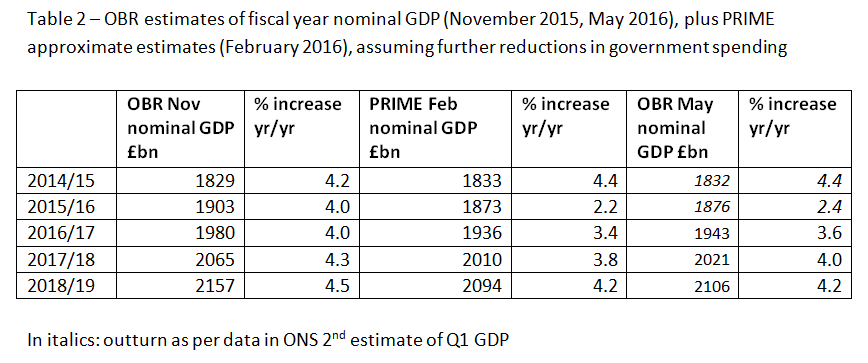

What we see is that on the OBR’s calculations, the size of the UK economy – in nominal terms – in 2018/19 is likely to be about £50 billion smaller than it had itself estimated as recently as November 2015. That is around 2.5% of GDP, not a small margin of error. It shows just how vulnerable and divergent official estimates of economic activity for a period of years ahead can be, even coming from the same source!

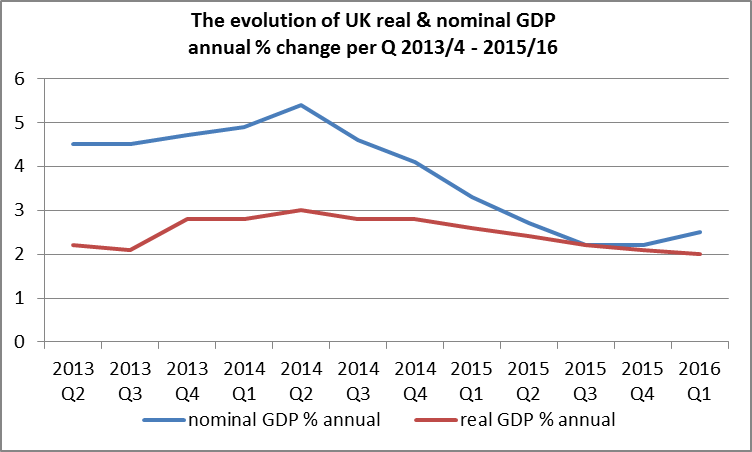

In fact, in their November 2015 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, para. 3.62, the OBR were still assuming nominal GDP growth of 3.6% in calendar year 2015:

“We expect annual nominal GDP growth to fall back from 4.7 per cent in 2014 to 3.6 per cent in 2015, largely reflecting slower quarterly growth of nominal GDP in the second half of 2014 that affects the annual growth rate in 2015”

This is a bizarre explanation, since it says no more than that the slowdown in nominal GDP is due to the slowdown in nominal GDP!

While low inflation or deflation means that government spending is likely to be less than estimated (assuming the same volume), it also means that government income will be well down – and by a greater percentage as the government plans on an increased tax take.

We also see that in Q1 in volume (“real”) terms, household consumption rose fairly rapidly (3.5% annual rate), but in terms of spending, the increase is more modest (2.6% annual rate). We also see that despite an increase in the number in employment, the “compensation of employees” (measured in current £) rose by only an annual rate of 3.3% in both Q4 2015 and Q1 2016. This confirms the trend of recent pay data showing that average real pay is only increasing – very slightly, and has not got back to pre-crisis levels.

The large majority of economists seem to hold the view that (at least a modest) deflation is good for the economy. There are of course many factors, but the experience of the UK over the last year is that this has not proved so. The economists got it wrong. The real economy has slowed precisely at the time that we have flirted with deflation. Deflation itself reflects in major part a lack of demand, and the lack of demand leads to weak economic activity.

One Response

You cannot induce deflation when the economy is slowing down (applying brakes and higher gear at the same time). You’ll be accelerating unemployment.