When looking at how economies are doing, we tend to look mainly at the trend in GDP. But in terms of economic well-being, a clearer (though still imperfect) indicator is GDP per head of population – how the economy is doing relative to changes in population.

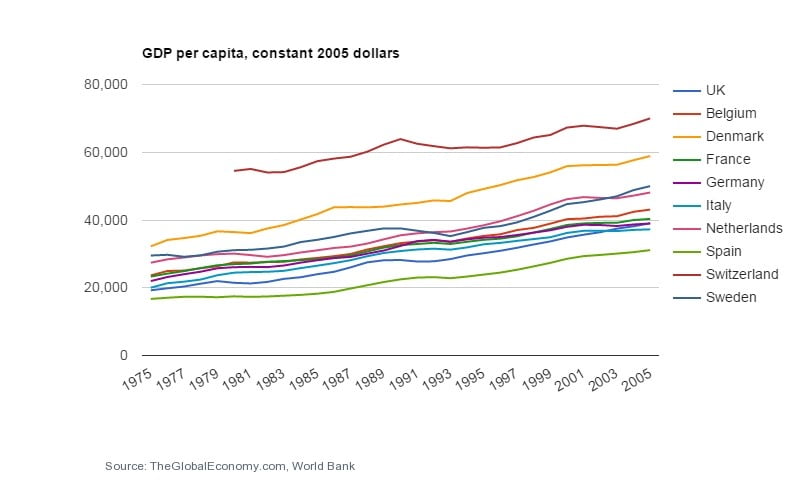

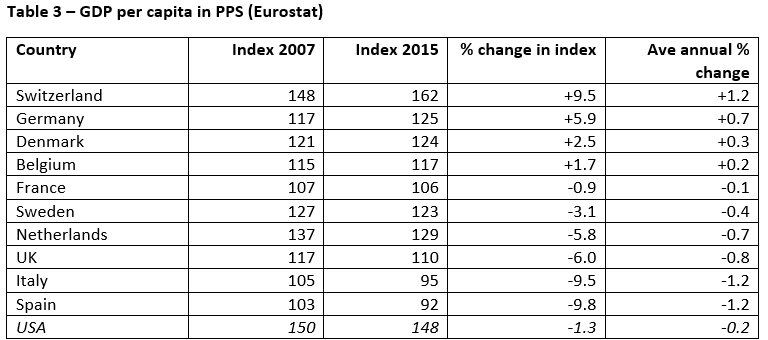

In general, since the end of World War 2, in most all so-called advanced economies, there was an almost inexorable upward slope in any chart on GDP per head of population. But over the last decade, and in particular since 2007-08, many countries – and notably those in Europe (especially the Eurozone) have reached a virtual plateau. In a few cases, there is still a tiny, upward glide. In others, the line is flat.

And in several cases, the slope is downward.

GDP per head Indicators

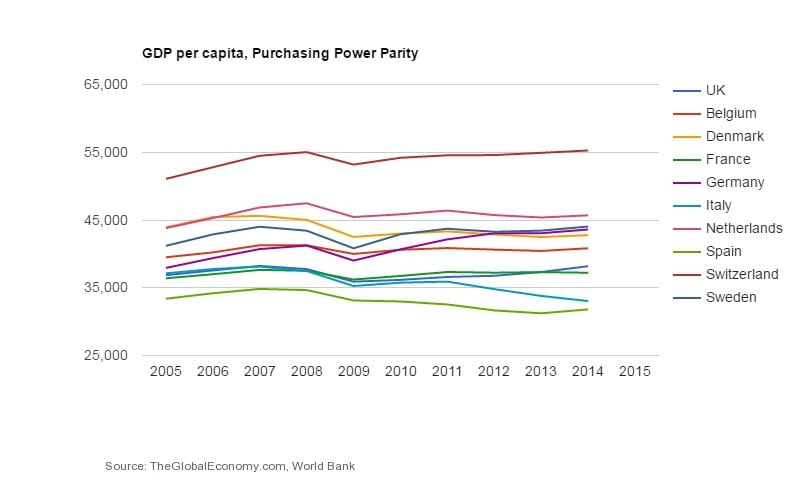

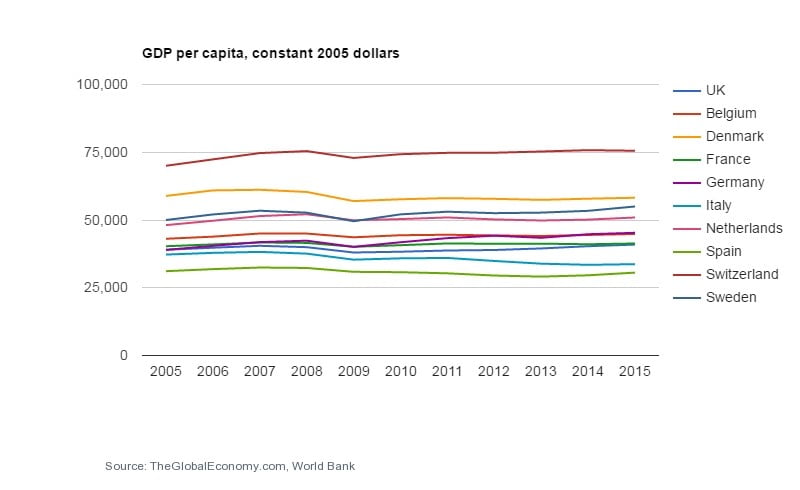

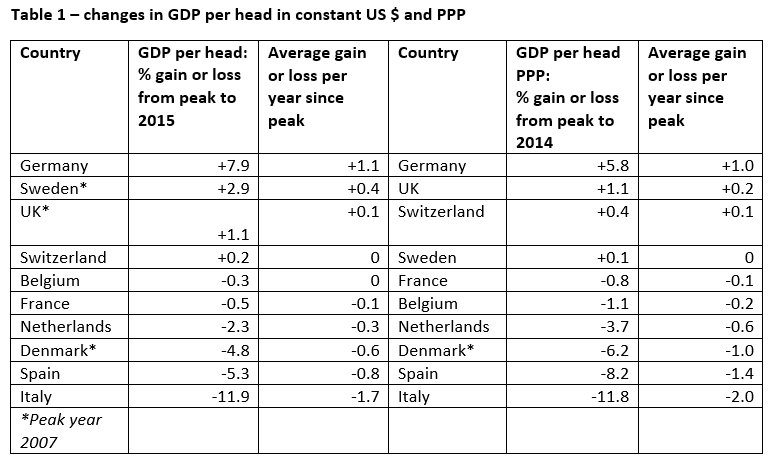

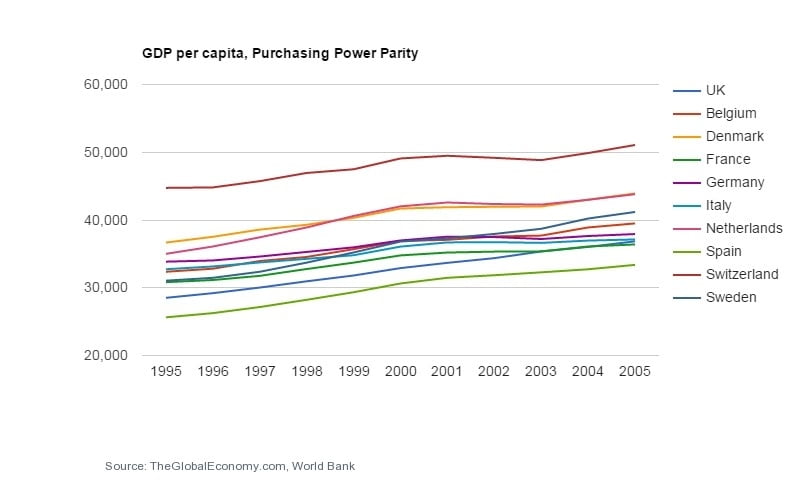

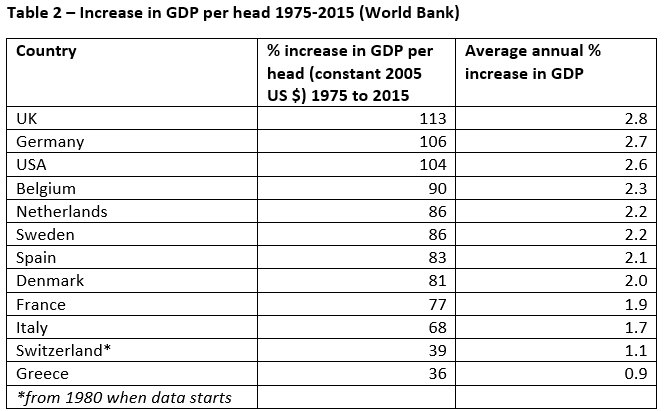

There are two indicators we can use for comparing trends in GDP per head. The first is simply to take real GDP (assessed in constant US dollars or in Euros), and the second is to look at GDP per head in purchasing power parity (PPP). I have taken both indicators, using data from the World Bank’s “TheGlobalEconomy” website – the first in GDP per head in constant 2005 US dollars, and the second in PPP [1].

I have taken a set of 10 European countries, EU members plus Switzerland, but excluding the central and eastern European joiners since 2004, whose development path is different, and looked at the changes in GDP per head since 1975. Six of the ten countries have been members of the Eurozone since it was set up.

The chart at the head of this article shows the position for GDP per head in constant US dollars from 2005 to 2015. Overall, I feel that the Flat Earth Society would feel quite at ease in this chart. For most of the lines are indeed, well, flattish – though with a financial crisis kink in 2009.

There were, on this indicator, 7 countries whose GDP per head was higher in 2015 than in 2005 – the three losers over the whole decade were Denmark, Spain and Italy.