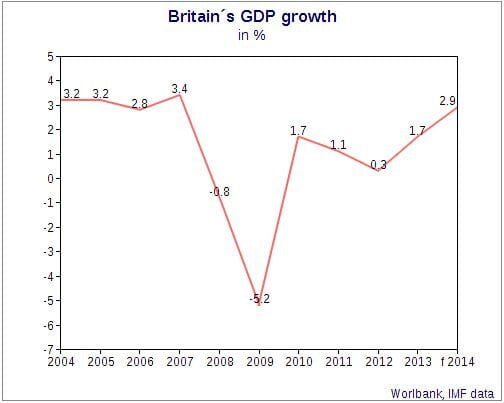

“While recent growth has been rapid, this is only because of the depth of the hole Britain dug for itself. Whereas in the US gross domestic product is well above its pre-crisis peak, in the UK it remains below previous highs and further short of levels predicted when austerity policies were first implemented. Not surprisingly given this dismal record, the debt-to-GDP ratio is now almost 10 percentage points higher than was forecast, and the date when budget balance will be achieved has been pushed back by years.”

Drawing on lessons from the Great Depression, Summers points out that US GDP rose by around 9% for a number of years after 1933, without this being seen as justifying the austerity policies that had helped to induce the Depression. Thus, he argues:

“..part of the story of British growth is simply one of catching up after a major crisis. Historically, deeper recessions are followed by stronger recoveries.”

Second point, in reality the Chancellor quietly changed tack when it became clear that the 2010 budget Plan A was failing (with GDP per person falling badly in 2012):

“The acceleration in growth has less to do with austerity spurring expansion than it does to a slowdown in the pace at which policy became more austere. Whether one looks at the deficit itself, or the various structural deficit measures prepared by national and international organisations, the pace of fiscal contraction has slowed over the past two years.”

This can be seen – we would add – from the annual GDP percentage changes since 2009. In 2010, the increase was 1.7%. This fell back to 1.1.% in 2011, and sank to a paltry 0.3% in 2012. The much-vaunted recovery in 2013 saw an increase in GDP of 1.7%, i.e. back to the same level as it inherited! It is also to be noted, as we have shown in PRIME, that GDP per head of population has only started to rise since the second half of 2013 – and is still only just back to 2005 levels!

And third point:

“Faced with the potential damage caused by the deficit reduction to demand and economic growth, the UK government has been forced to introduce a number of extraordinary measures to support lending.”

Summers singles out “Help to Buy” as being highly problematic. While the stated aim of austerity was to improve ‘confidence’ in the UK as sovereign borrower,

“guaranteeing mortgages en masse is creating a huge potential government liability, as do other loan guarantee programmes.”

Moreover, subsidised credit for private housing is likely to lead to asset bubbles. As we have argued, the government has encouraged the rise of private demand without increasing productive assets in the economy – the number of new dwellings remains historically very low. This naturally inflates house prices and increases the liability of the government which backs these mortgages.

In conclusion, he argues that Britain’s recovery to date reflects a combination of the “depth of the hole” we found ourselves in, the “moderation” in the trend to ever-deeper austerity, and the effects of bubble-inducing government loans or guarantees.

So while he concludes (a little ironically, we feel) that all this “may be better for the citizens of Britain than any alternative”,

“It certainly should not, however, be seen as any kind of inspiration to other countries.”

One Response

Larry Summers is a boring idiot. In the last sentence of his famous “secular stagnation” speech at the IMF at the end of last year, he claimed that a “zero nominal interest rate is a chronic and systemic inhibitor of economic activity”. Clueless.