This article was first published in German on Makroskop

Brexit Fallacies

In its conception and subsequent practice the European Union was and is more than an economic union to facilitate free movement of trade, capital and people. Drawing on that broader EU vision, those in Britain wishing to exit the EU never tired of accusing the “bureaucrats in Brussels” of seeking a European “super-state”. With few exceptions, those advocating continued membership campaigned as if the European Union were nothing but a customs union.

And that is why Brexit won (albeit narrowly). The case for Remain by Tory Chancellor George Osborne was the neoliberal globalization argument scaled down to the European continent. In contrast, when not indulging in rampant xenophobia, the Brexiters presented membership as a question of national “sovereignty”.

Contrary to all expectations, the mainstream pro-EU campaign was more negative than the blatantly xenophobic Brexiters. The former sought to instill fear of the dire economic costs to every household of leaving the European Union, while the Leavers wrapped their reactionary campaign in an illusory hope that “regaining sovereignty” that would bring a better Britain for all.

Both campaign strategies were cynically misleading. The alleged economic costs predicted by Remainers were at best reasonable but unverifiable guesses, always presented as expert consensus. A rational debate on economic costs and benefits might have enlightened voters. In practice what the government presented as economic analysis was thinly-veiled propaganda, especially the notorious “long term” impact study by the UK Treasury.

The duplicity of the official Remain campaign paled before the misrepresentations of the Leavers. The many detailed misrepresentations, such as the claim that leaving the EU could free money to fund the National Health Service, were minor compared to the biggest mendacity of all, that by leaving the European Union Britain would regain national sovereignty. Most shockingly duplicitous were the few nominal progressives that repeated this crass appeal to nationalism.

Britain is not a member of the euro zone, and like Denmark has an explicit legal exception to the rule requiring EU members to join the common currency. In addition, the UK government has refused to adopt the infamous “fiscal pact” that is the primary source of the European Commission’s power to dictate economic policy to member states. The only effective enforcement powers held over Britain by the “bureaucrats of Brussels” are those that every concerned citizen should support: consumer, environmental and workplace protection.

The mainstream Remainers appear to have learned nothing from losing the referendum through their failure to make a positive case for EU membership (see the EREP pamphlet published shortly before the referendum to which I contributed). Now they seem intent on repeating the dubious dire warnings that allowed them to snatch Brexit from the jaws of Remain. Perhaps most absurd is the suggestion that in these perilous times, only the sitting governor of the Bank of England “stands between Britain and economic chaos”. Given the dubious consequences of the Bank of England’s “quantitative easing”, Governor Mark Carney seems an unlikely saviour.

In the context of this gathering Brexit hysteria, we need to sort the sense from the nonsense. In specific, its is necessary to identify sound reasons to worry about exiting the European Union and by doing so to develop a strategy based on reality not on unfounded fears. A logical beginning is the anxiety over the Brexit impact on UK trade.

Trade: Misplaced Anxiety

Before the referendum the mainstream Remainers tried to sell EU membership with “free trade” arguments. They invoked the old cliché that “everyone gains from trade”. They warned that leaving the EU would drastically reduce UK access to European markets. The same people now repackage that unsuccessful argument. “We are doomed to economic collapse if we leave” has become “doom is upon us”. However, economic data since June suggest little weakening of the UK economy much less disaster, as shown in recent statistical work published by Prime Economics.

The post Brexit recession that many predicted has not occurred. The prediction of economic contraction derived largely from fears of loss of export sales to the continent and decline in inward foreign investment. A moment of rational reflection indicates that these effects should not be immediate. The rules governing how UK companies operate in the European Union remain the same as they were before the referendum and are unlikely to change in the near future.

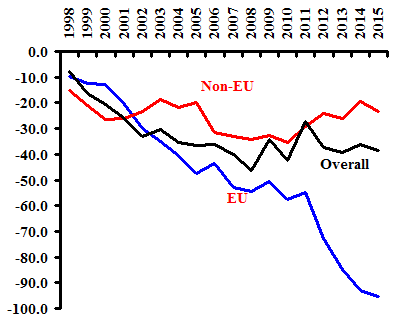

If exports generate employment and provide a domestic demand stimulus for growth is correct, then that implies its obverse, that imports reduce employment and domestic demand. To put it simply, if exports generate employment, imports must reduce it, and the export-import balance measures the benefits of trade. With this simple logic in mind, the chart below shows the overall UK trade balance in goods, the balance with the European Union, and with the rest of the world.

Since 1998 the UK trade balance with the European Union has fallen almost continuously, from about minus £10 billion to almost minus £100 billion, with a sharp plunge after 2011. The trade balance with the rest of the world changed much less, fluctuating between minus £15 and minus £30 billion.

Since 2000 British exports to other EU countries stagnated. In 2015 goods exports were only 5% above 2000 in volume terms and 14% below 2008. We can attribute the latter decline to slow EU economic growth. The miserable growth performance resulted from policies of fiscal austerity, policies unlikely to change. The contrast with non-EU trade is striking, up over 75% since 2000 and 35% since 2008 (again in volume terms).

To date the UK government’s strategy for negotiations is unclear. Therefore, whether the terms for leaving the European Union will make access to other markets easier or more difficult is a matter for speculation. Fear of export decline as a result of leaving the European Union should not at the moment be a serious source of anxiety, though that may change.

UK balances for trade in goods: overall, EU and non-EU

1998-2015 (£ billions)

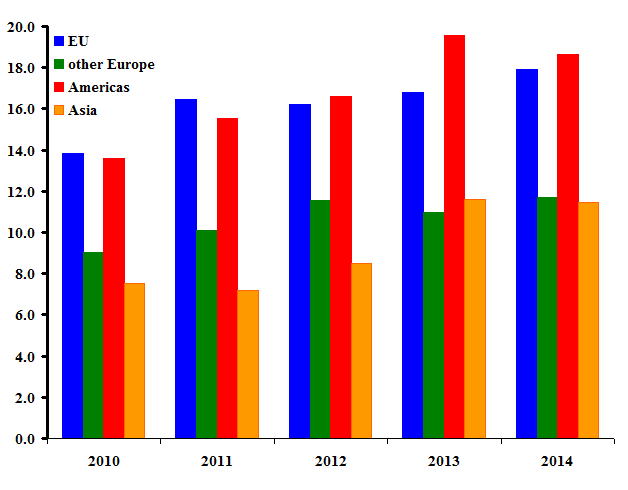

In addition to goods exports of £292 billion, UK companies had service exports of £119 billion in 2014 excluding finance and transport. The second chart shows the service balance for four country groups, the European Union, other European countries, the Americas and Asia (with Africa the small residual).

The balances for all four are positive, and for the last three years the largest surplus came with the Americas, the United States and Canada by far the most important. Over the five years service exports expanded by about 35% for all four groups, suggesting that EU market access rules are the major determining factor for growth.

The fate o service exports by the banking sector, not included in the chart, raise serious measurement, analytical and policy issues. For decades if not generations critics have attacked the financialization of the UK economy, attacks rejuvenated and reinforced by the global financial crisis of 2007-2010. Both the potential instability fostered by an excessive banking sector and its collateral effects on inequality and de-industrialization (see OECD study) suggest that should Brexit weaken British banking the long term consequence might not be negative.