“What the sofa gives, the sofa can easily take away” – Robert Chote, speech to the Scottish Parliament Finance Committee, Edinburgh, January 6 2016

With the budget just a couple of months away – it will be on 16th March – we can make at least one prediction: it will be a lot tougher than the Chancellor hoped, and many believed, back just a few weeks ago. And it seems likely we will all pay the price.

In his Autumn Statement speech on 27th November 2015, the Chancellor said:

“The OBR expects tax receipts to be stronger. A sign that our economy is healthier than thought….[D]ebt interest payments are expected to be lower – reflecting the further fall in the rates we pay to our creditors.

Combine the effects of better tax receipts and lower debt interest, and overall the OBR calculate it means a £27 billion improvement in our public finances over the forecast period, compared to where we were at the Budget…

First, we will borrow £8 billion less than we forecast – making faster progress towards eliminating the deficit and paying down our debt. Fixing the roof when the sun is shining.

Second, we will spend £12 billion more on capital investments – making faster progress to building the infrastructure our country needs.

And third, the improved public finances allow us to reach the same goal of a surplus while cutting less in the early years. We can smooth the path to the same destination.”

The turbulent economic start to 2016 has already made this speech sound hubristic – and Mr Osborne has sought to get his defence in first, blaming foreigners for the likely slowdown with their “dangerous cocktail of new threats”. But he tells us, this year is “mission critical” in his resolve to make “the biggest reduction in government consumption outside demobilisation in over 100 years.”

In November, the Chancellor escaped from a nasty politico-economic trap around his earlier plan to drastically cut the incomes of those on working tax credit, thanks in large part to a series of small shifts in their future economic estimates by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

In his speech to the Scottish Parliament Finance Committee on 6th January, Robert Chote (OBR Director) sought to defend the OBR against charges that – in their Economic and Fiscal Outlook of late November – they had been, let us say, over-responsive to the shorter-term political needs of the Chancellor:

Lots of people latched onto the £27 billion that we had apparently found down the back of the sofa over the next five years. The biggest contributors to this aggregate improvement in the budget balance were a fall in the Government’s prospective debt interest payments, the recent strength of some tax receipts and changes to the way we forecast VAT and National Insurance Contributions.

He quite fairly points out that

…£27 billion is not as much as it sounds. Over five years it corresponds to an average downward revision to the budget deficit of one quarter of one per cent of GDP. This is pretty small beer in an economy where the public sector is spending around 40 per cent of GDP and raising about 36 per cent of GDP in revenue – and where the average error forecasting the budget deficit just over the rest of the fiscal year at an Autumn Statement is around ½ per cent of GDP.

But what matters most is what Mr Chote does not say – that the (in themselves) relatively small changes in the near-term almost all fell on the side of optimism, evidently helpful to a Chancellor in a tight political spot, at a time when the economic and fiscal data were giving the opposite message, that the economy was in fact slowing.

Thus, on 27th November – just two days after the OBR’s Outlook, but surely shared between them – the ONS published its second estimate of GDP for Q3 2015, which already showed that the economy was decelerating quarter by quarter.

According to this estimate, constant volume (“real”) GDP had increased at an annual rate per quarter of

Q4 2014 3%, Q1 2015 2.7%, Q2 2.4%, Q3 2.3%.

Nominal (current price) GDP over the same period slackened from an annualised rate of 4.2% (Q4 2104) to 3.7% then 3.4% and (Q3) 3.4%.

Yet despite this evident slowdown the OBR (while leaving real “growth” for 2015 unchanged at 2.4%) decided to increase its estimate of GDP for 2016 and 2017 by a little nudge, from 2.3% to 2.4% for 2016, and from 2.4% to 2.5% for 2017.

This small change, added to others, had the effect of slightly improving (lowering) the headline figures for public debt and deficit (as % of GDP), which gave the Chancellor more political space in the shorter term. With one small leap, he was free of the self-imposed fiscal need to cut working tax credits (the task still ultimately being achieved by cuts to Universal Credit).

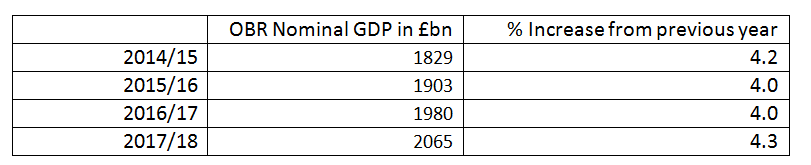

The OBR continues to assume (see its very helpful database) that nominal GDP for the year 2015/6 will increase at the annual rate of 4%, next year (2016/7) by 4% and the year after by 4.3%.

Given the continuing fall in commodity prices, and the deflation/disinflation that has become more embedded, these assumptions also seem highly questionable. Yet they are relevant to the OBR and government assumptions about public finances, since tax receipts are paid in current pounds, not “constant volume” pounds. Thus (to simplify) if you spend £120 in a shop in each of two years, but in the second year get 50% more stuff in volume due to deflation, real GDP rises but nominal GDP remains unchanged. And the government gets VAT income of just £20 in each year, i.e. a zero increase.

But the OBR’s forecasts took another, more serious, knock just before Christmas, when the 3rd estimate of GDP for Q3 2015 was published by ONS. In this, the annual rate of GDP increase per Quarter was reduced by ONS for each of the last 4 Quarters. More remarkably, the ONS’s estimates for nominal GDP were reduced much further – but in reality coming more in line with what one would anticipate with near-zero inflation. Here are the ONS’s old (Nov) and new (Dec) annual percentage assumptions for the last 4 Quarters: