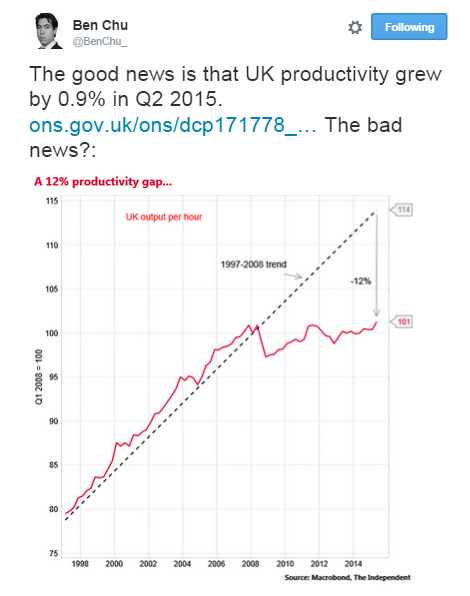

Powerful stuff (though as you see above, the ONS say the gap is an even bigger 15%). And it is this stasis in labour productivity improvement over a period of years that has caused so many to fret about the UK “productivity puzzle”, wondering why it has stagnated.

We have long been of the view that – far from being a mystery – the basic answer is that productivity is mainly driven by demand. And demand has been strongly held back by the government’s economic policies which have led to the slowest recovery in recent decades.

But since only supply-side economics are in fashion among the economics mainstream, this issue of demand is largely ignored. Of course, the UK’s ultra-flexible labour market also plays a role, since it is often easier to substitute labour for capital than in ther countries (see for example my comparison of the UK and France – same GDP and population, vastly different productivity)

While it can be argued that, over time, improved productivity leads to faster-rising GDP, the reverse causation is far more plausible as the dominant factor in any specific shorter period. Here is a chart made wholly from ONS data showing the annual percentage change on a rolling 4 quarter basis of three elements – output per worker, output per hour worked, and GDP. The correlation is very strong. When GDP increases, so does labour productivity. When GDP falls, and in particular in recessions, labour productivity falls.

4 Responses

Demand, yes, and more efficient use of capacity. But I would argue (and I did here several years ago: http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue63/Harvey63.pdf) that the motivation is higher when the labor resource is scarce to create efficiences, whether by finding technologies, shifting workers to more productive tasks, or streamlining processes. The idea that technology in and of itself drives productivity is almost universally assumed, but there is much more evidence that the unemployment rate itself is the instigator. High demand, of course, usually means low unemployment.

So in addition to the more efficient use of capacity (note too, that as Steve Keen and others have pointed out, and despite the orthodox assumption of rising marginal cost, in the real world, marginal cost is almost always flat or negatively sloped.

I agree. In Capital I, Marx makes precisely this point in relation to the introduction of new technologies and techniques, in response to both rising wages, and the higher costs imposed on capital due to the introduction of the Factory Acts. He points out that earthenware manufacturers claimed that they could not possibly survive with those restrictions, but when they were introduced, they developed new technologies that raised productivity, which in turn reduced costs, and increased profits, which in turn led to additional accumulation, and higher levels of employment.

Adam Smith himself pointed out that wherever wages are low the price of labour is high, meaning that low wages encourage capital to engage in low value types of production, and to fail to invest in means of raising productivity. Marx points out that, at one point capital even used women to pull canal barges rather than horses, because the former was cheaper!

You are absolutely correct about flat, and more often falling marginal cost curves, a reality that is routinely denied, or simply not assumed by orthodox economics. It is one of those fallacies along with the idea that the value of commodities, and the value of national output can be resolved into factor incomes – wages, rent, profit and interest – that was promulgated by Adam Smith, and accepted by orthodox economists like Keynes, but which even some Marxist economists today fail to recognise.

As marx points out, the Physiocrats were actually in advance of Smith in that regard, but the failure to understand that Gross National Output and Gross National Income are not the same lies at the heart of many inadequacies today. As Marx and the Physiocrats recognised, the value of Gross National Income is only equal to the new value created in the year by labour, in other words, it is equal only to the value of the consumption fund, whereas the value of gross national output also includes the value of the means of production used in the production of means of production – exchange of capital with capital rather than revenue – which in turn must be reproduced out of the value of total output.

In Marx’s terms, gross national output is equal to C + V + S, as with the value of any commodity, whereas the value of National Income is equal only to V + S, the new value created by labour.

I agree, about the role of demand. This was well known and accepted by economists in the 1970’s, who recognised that as economic activity slowed, and capacity utilisation fell, unit costs of production rise.

There is one other point I’d make here though. The measurement of productivity here is in terms of output value. However, a real measurement of productivity should be undertaken in terms of physical quantity of output. If I introduce a new machine, which doubles the quantity of units produced, this represents a doubling of productivity, as Marx sets out in Capital I. But, this rise in productivity will also cause a fall in the value of each unit of output.

Its conceivable, therefore, that real productivity may double as a result of the introduction of this new machine, but that same rise in productivity, results in no rise in total output value. In any event, the rise in output value, will be less than the actual rise in productivity measured by quantity of output.

Yet, as Marx again describes in Capital III, and in Theories of Surplus Value, it is this actual physical output that is decisive here, not the output value.

The machines and materials used in production have to be physically replaced on a "like for like" basis "at least in terms of effectiveness", and so if productivity results in the value of these machines and materials falling, a smaller proportion of society’s total output/social labour-time has to be set aside for this replacement.

Similarly, it is workers real not nominal wages that are important, although it may be necessary to use "money-illusion" to effect this given that wages are "sticky downwards". So, if more wage goods are produced physically, as a result of a higher productivity, again a smaller proportion of society’s total social product/labour-time has to be devoted to reproducing labour-power, which in turn means that the proportion of the total social product/labour-time that constitutes surplus product/value rises.

This rise in surplus product/value combines with the lower value of means of production, thereby facilitates an increased accumulation of capital in terms of mass, even if the value of this capital is nominally reduced. Indeed, this reduction in capital-value is a direct result of the rise in productivity, as less social labour-time is required for its production.

This is the point made by Marx in Theories of Surplus Value, where he supports the position of Ricardo as against Smith, where Smith states that Smith placed too much emphasis on the gross social product, and not enough on the net social product, i.e. the surplus value.

Ricardo argued that it was far better to have a situation of higher productivity, where 200 workers are able to produce enough to support a population of 300, than to have a situation where 300 workers are required to produce enough to support a population of 400, even though in terms of total output value, the 300 workers would produce a greater mass and value of output.

The point being that out of the total product of the latter only 25% is available for accumulation, whereas in the former, 33.3% of the total product is available for accumulation.

I don’t think that is the explanation for current low levels of productivity in Britain, however. Rather its more like the under employment that existed in Eastern Europe. Large numbers of workers employed on zero hours contracts, and who have become self-employed gardeners and window cleaners, because they can’t get permanent jobs, are only actually employed producing anything for a small proportion of the time, even if they spend large amounts of time, trying to find work for themselves.

Anyone in business will tell you that without demand their is no purpose to production, Production without sales results in bankruptcy.

More demand than production generates inflation

More production than demand generates deflation

But then I’m only a simple shopkeeper so what do I know.